When Chikkaballapur-based farmer Rajesh (name changed) worked briefly in an office in Bengaluru, he put on some weight. To shed the extra kilos, he replaced his breakfast and dinner with a shake, as prescribed from a leading global nutrition company. The shake includes protein, mineral and vitamin supplements and is expected to make a person feel full.

Far from improving his health, Rajesh suffered renal failure in his early 50s after nearly six years of substituting his meals with the weight loss supplement. Since he had no pre-existing health issues, his family attributes this to the supplement.

He now undergoes dialysis twice a week at a private hospital in Chikkaballapur, spending Rs 1,000 to 2,000 per session. Due to his ailments, Rajesh is unable to continue agricultural work as usual, he is confined to doing basic tasks. He needs a kidney transplant but is unable to find a donor.

This outcome is not limited to Rajesh alone. Across the country, many have similar stories.

Bengaluru-based nutritionist Pallavi Idoor has had several clients whose supplement consumption for weight loss led to hormonal imbalance and gastrointestinal issues among other complications. “These are protein supplements with high sucrose content, which are marketed as a replacement for meals,” she says. Users who have a sedentary lifestyle and an unhealthy diet have an increased load on their liver and kidneys when they use such supplements, she adds.

“In the initial stages, the negative effects can be reversed by stopping the supplement and making dietary changes, but long-term use could cause permanent damage,” Idoor says, adding that people with pre-existing health problems are more vulnerable.

Idoor clarifies that high-quality protein supplements can be used by those with an active lifestyle as a post-workout drink.

Even such use should be with caution, the owner of a gym and trainer in Bengaluru explains, as several companies are marketing protein powders directly to gyms now. “Their agents take products to gyms and do demos as well. These products are expensive and have high margins. A 2 kg tin can cost Rs 2,000 to 3,000 and the margins would be Rs 600 to 700. Besides, young people joining gyms want quick results. So, gyms sell these products both for profits and to attract more customers.”

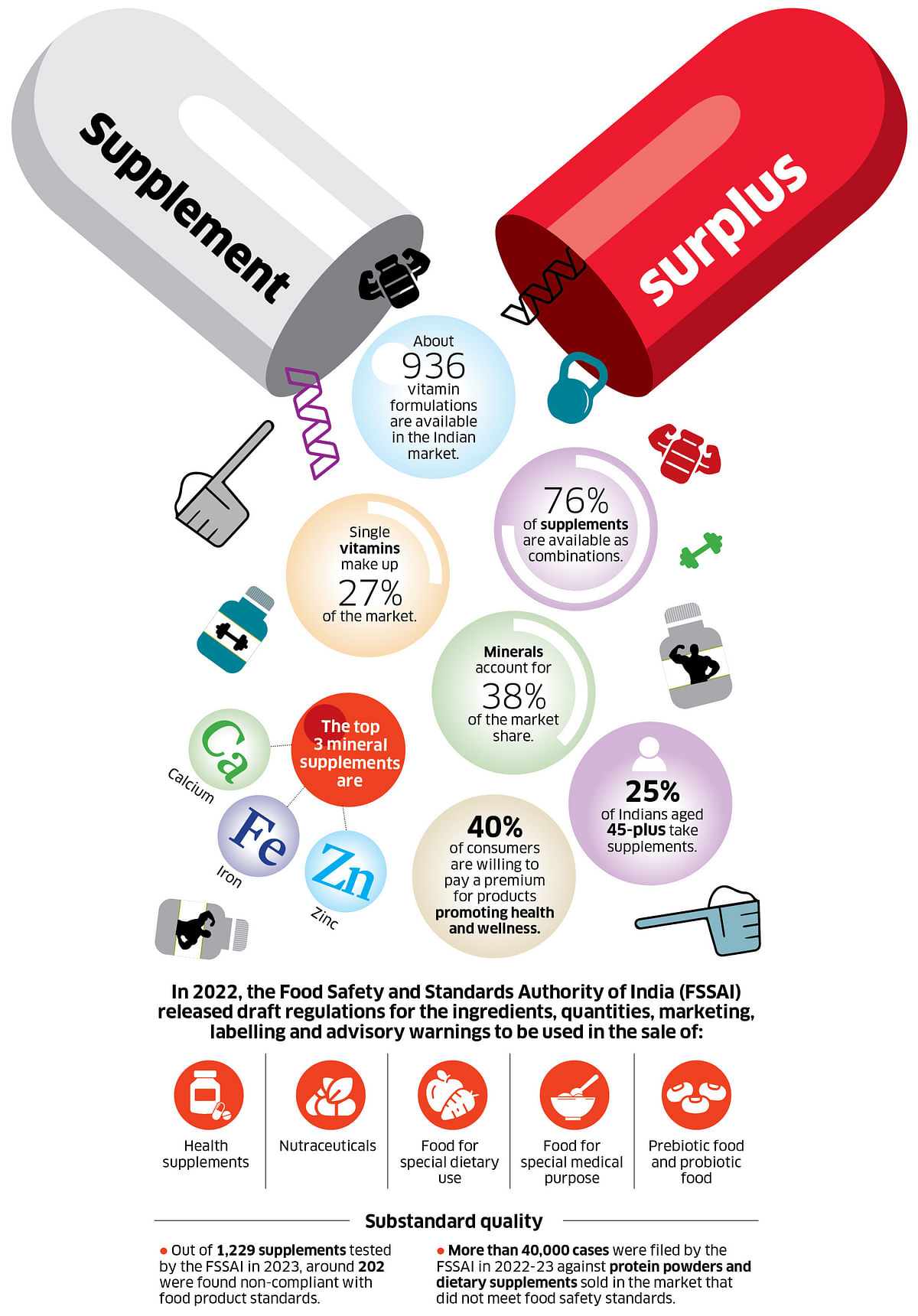

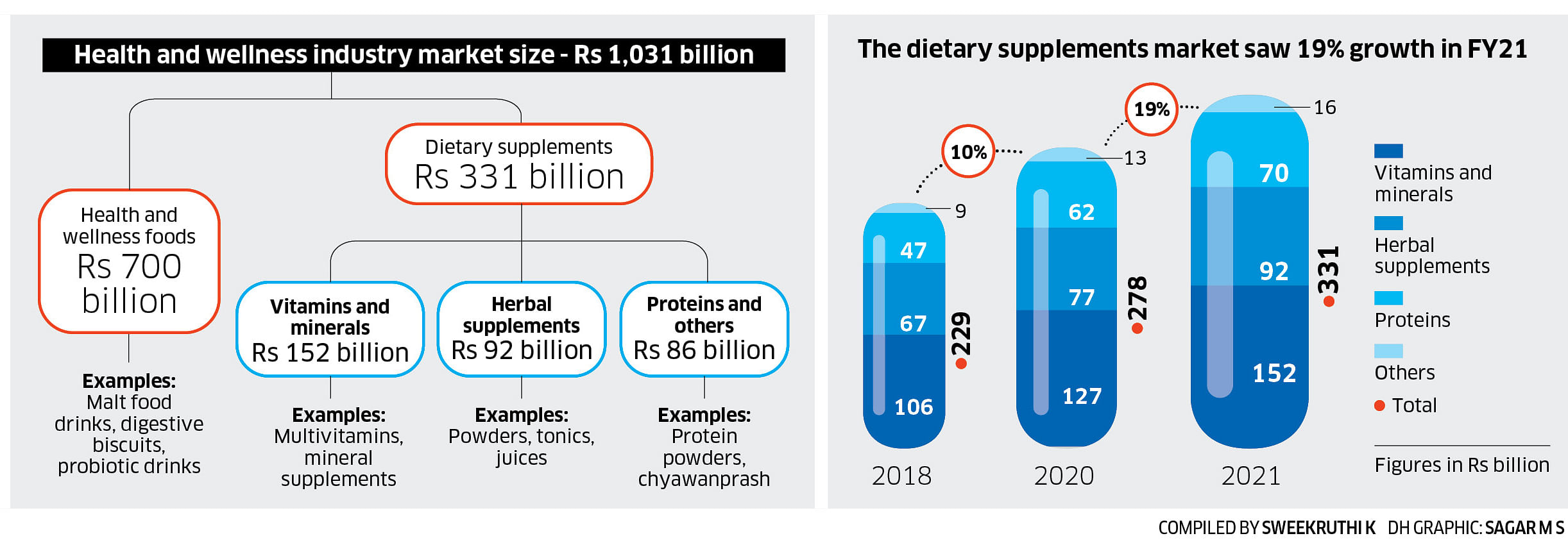

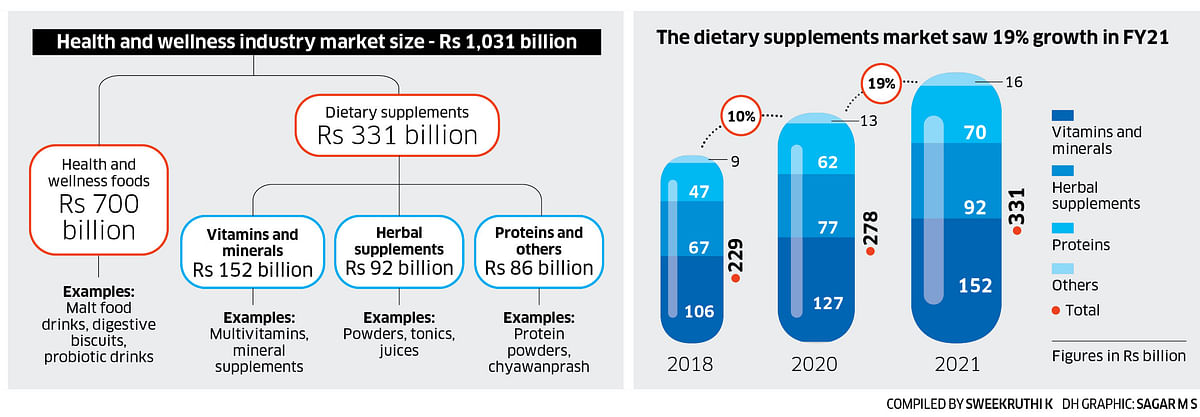

People across age groups have increasingly come to depend on supplements to improve their overall health or help cure diseases. As a result, several fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) companies are entering the market, introducing easy-to-eat products like vitamin gummies.

But users should be careful, explain doctors. “People generally believe that herbal supplements are completely harmless, but now there are studies providing evidence that it is not so,” says Dr Rajkumar Wadhwa, head of the organ transplant centre at a hospital in Bengaluru.

A US-based study, published in the journal Liver Transplantation last year, found that, between 1995 and 2020, the proportion of patients requiring liver transplant due to herbal or dietary supplements (HDS) use had increased eightfold. Among the total patients with drug-induced acute liver failure, the proportion of HDS users had increased from 2.9% to 24.1%.

At the organ transplant centre, exclusively for liver patients, cases where immunity-boosting supplements likely contributed to liver damage are fairly common now, says Dr Wadhwa. “Multiple factors are involved, so we cannot prove it. But based on clinical history, we strongly suspect that these supplements are contributing to liver failures.”

Easy approvals

Modern medicines have stricter approval and regulatory processes under the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation. But nutraceuticals are considered food products and are regulated by the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI).

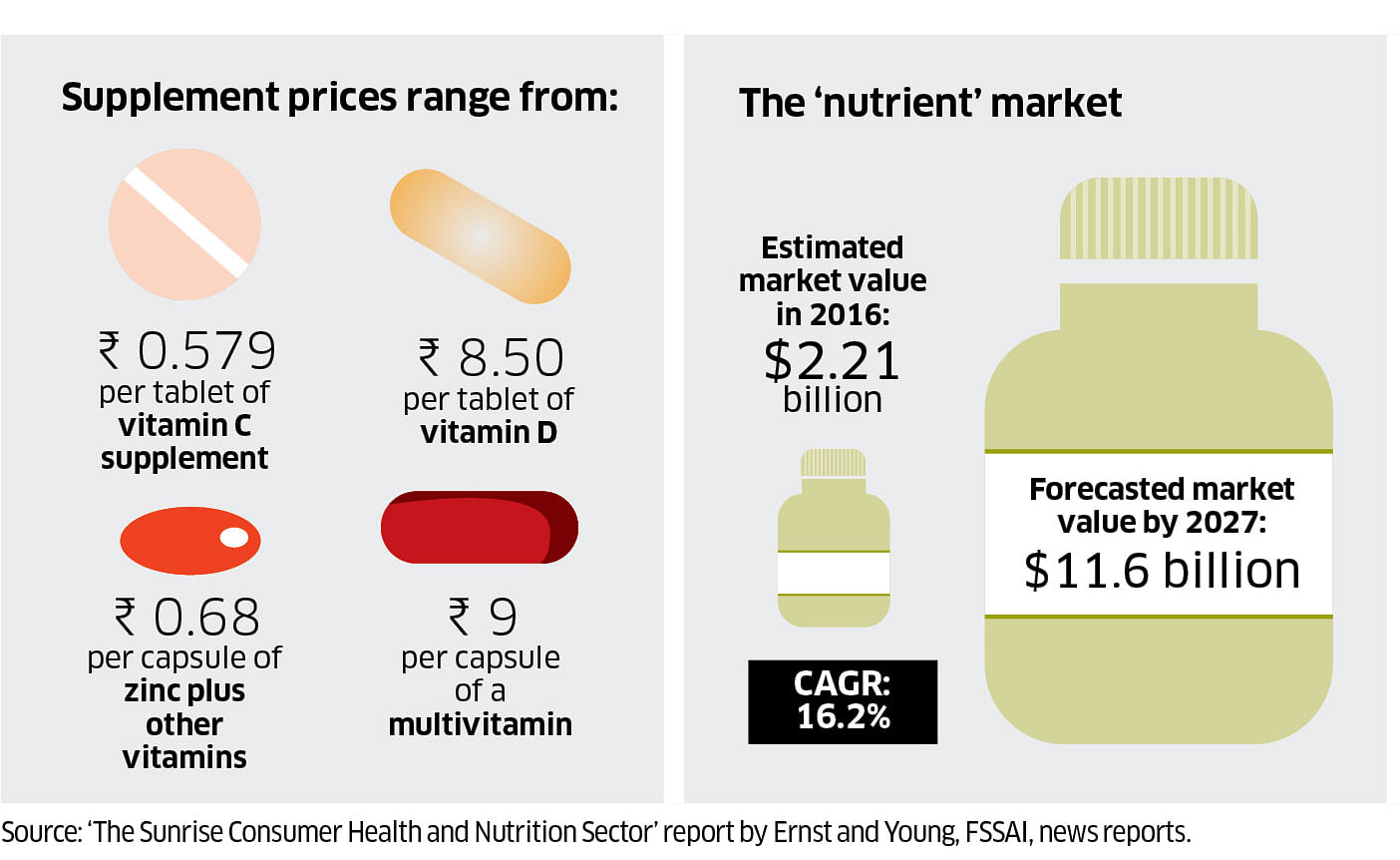

These products can range from multivitamins to herbal juices and protein supplements. They are easily available over the counter, through online platforms and direct marketing, and the costs vary widely.

FSSAI’s approval process for new products is relatively simple. It has a list of ingredients, each with either a daily Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) or a permissible range. “So to get a product licensed, you need to submit the list of ingredients that are from FSSAI’s list, their quantities, and also mention the product’s serving size and delivery format (whether capsules, extract, etc). The product should also meet some guidelines — if it is a vitamin supplement, specified compounds should be present in a certain amount,” says Ramesh Agarwal, CEO of a consultancy that helps food companies get FSSAI approvals.

Nutraceuticals are often marketed with claims that are hard to verify, such as blood pressure regulation or improving joint health.

Most companies do not conduct independent trials to establish these claims, says Ramesh Agarwal. “They can make ingredient-based claims based on previous studies or literature,” he adds.

Suppose an Ayurvedic text says that ashwagandha increases energy levels, or a reputed research article says curcumin (a compound available in turmeric) is good for stress reduction. If a product contains curcumin or ashwagandha, then it can be marketed as increasing energy levels or for stress reduction.

Only when a manufacturer wants to introduce a completely new ingredient to the Indian market, or make a claim for which scientific evidence is not available, they have to conduct clinical trials, he says. “While big companies do such trials, many small companies may not have enough resources to conduct them.”

There is regulation in place to ensure supplement manufacturers are not claiming to cure or mitigate a specific disease, as per the FSS (Nutra) Regulations, 2022. However, in practice many companies make exactly these claims.

Active compounds unidentified

Apart from products that need approval from FSSAI, Ayush products are also popularly used as supplements. Obtaining approval for classical ayurveda products is easy. But to develop a new product, ingredients should be selected from among the 1,800 herbs permitted under the Drugs and Cosmetics Act (DCA). Shrikumar, general manager at an Ayush company, says that the rationale for selecting these ingredients and their efficacy should be proved through clinical trials. “The sample size for these trials range from 50-200, depending on the target population.”

Proponents of modern medicine have been questioning the safety and efficacy of herbal drugs, as there is no clarity on how they work.

Of the 1,800 herbs in the DCA, measurable chemical constituents have been identified in only 100 to 120, says Dr Amit Agarwal, CEO of an Ayush company, and a member of the Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission that sets standards for drugs. These are herbs like ashwagandha and brahmi that also have an export market.

The push to identify the constituents in these products came about due to guidelines in countries like the USA and the UK. The guidelines ask for the identification of the active compound that causes the herb’s medicinal activity or a marker (a chemical constituent).

“Though chemical constituents have been identified in about 120 herbs, there is consensus about the active compound in only around 25 of them. There are hundreds of compounds in each herb. Even when a particular compound is identified, it is difficult to say that it is causing the herb’s activity,” says Dr Amit Agarwal, who has been conducting and advocating for more research into active compounds.

Though the science is not yet clear, he believes herbal products are safe if uncontaminated and consumed in the right doses. “Often the herb gets blamed while pesticide contamination or mycotoxins (toxins from fungi) could be the cause. A recent Danish research paper said that ashwagandha consumption caused some people to fall sick, but the product that was tested contained ashwagandha leaf extract, and not root extract, as is required,” he says.

Contamination from pesticides, heavy metals and microbes is a major concern. With the wide use of pesticides now, getting hold of clean material is a challenge, explains Dr Amit Agarwal. “Washing cannot remove pesticides embedded into the tissue. And these materials get more concentrated during extraction. If 100 kg of herb is concentrated into a 10 kg decoction, the concentration of pesticides will also increase,” he adds.

However, emerging studies from India clearly show toxicity from certain herbs themselves, and not from any contaminant. A study on giloy, which was marketed as an immunity booster during Covid, showed that it is associated with herb-induced liver injury with autoimmune features, in some patients. The study, published in the journal Europe PMC last year, was conducted among 43 patients who came in with acute hepatitis associated with giloy consumption, across nine states including Karnataka. The study found that the giloy samples they had consumed did not have any other contaminant, such as pesticides, that could have damaged the liver. Other causes for liver damage were also ruled out in these patients.

Around 10% of patients died within two months of presentation, and nearly 5% needed liver transplant within three months, says the study.

A scattered industry

The supplements industry currently has thousands of small players scattered across the country, making regulators’ task tough.

The supplements industry also has a large number of third party manufacturers — who make the product and supply it to the brands that sell it — that are hardly regulated. A third party manufacturer based in Bengaluru says, “Some brands quote very low amounts for the product. For example, for a product that would cost Rs 2,000 per unit to manufacture as per standards, they would quote Rs 600. If we do not accept this amount, there are other manufacturers who easily supply low-quality products at that cost.”

FSSAI, in general, relies on self-regulation by food companies. Occasionally, officials collect product samples from stores and test them.

A food safety official from a South Indian state says, “The cost of nutraceutical products from major brands range from Rs 4,000 to Rs 15,000. To test one brand, we have to buy four samples of their product, so this will cost us at least Rs 16,000. Whereas the average amount we get from FSSAI to test four samples from one brand is Rs 600.”

If a drive is conducted where samples from 10 brands are collected, the cost of buying the products alone would come to over Rs 1.5 lakh. Hence nutraceuticals are not tested routinely, unless FSSAI gives directions for a separate drive, says the official.

Testing is expensive too. The FSSAI has earmarked an expenditure of Rs 19,000 per sample as payment to accredited private labs for nutraceutical testing. Most states, including Karnataka, do not have government labs that are accredited to test nutraceuticals, and hence send samples to private labs.

Dr Amit Agarwal says that not enough enforcement is happening from the Ayush department too to tackle the substandard Ayush products in the market. A private lab associated with his company was accredited over 10 years ago to test samples collected by the department. It gets fewer than 20 samples from the department annually.

This March 7, FSSAI issued a notification to all states to conduct special enforcement drives on nutraceuticals. The notification said that various supplements in the market were not compliant with the FSS (Nutra) Regulations 2022, and that products were marketed with false and exaggerated claims, violating the FSS (Advertisements & Claims) Regulations, 2018.

It also asked states to ensure a strict vigil on the manufacture and sale of these products. States were supposed to submit reports of their drives by March 31, this year. However, Karnataka has not conducted a drive on nutraceuticals so far. Dr Shamla Iqbal, the state’s Food Safety Commissioner, says it will be taken up soon.

FSSAI has not responded to DH’s queries about the number of states that have completed the drive. A drive was conducted in Himachal Pradesh in June after the National Human Rights Commission issued notices to the union health ministry based on media reports of spurious nutraceutical production.

Last year, after a young person died, Karnataka conducted a drive, investigating protein powders sold at gyms. This drive, based on the directions of former Health Minister Dr K Sudhakar, found that two-thirds of collected samples (54 out of 81) were misbranded — the products were not labelled correctly or did not comply with the claims on the label. Legal action against the companies is still ongoing.

Aggressive marketing

Other than implicit faith in natural products, aggressive multi-level marketing (MLM), especially by global nutrition brands, is also contributing to a rise in supplement use.

These companies have routine meetings, follow-ups and cultural events, where existing users market products to new users. Bengaluru-based Bharathi B V says that she was introduced to a product by an acquaintance while undergoing breast cancer treatment in 2014.

She used the product as she was unable to exercise during her cancer treatment and had put on weight. “I replaced my breakfast with their weight loss product for 18 months, and my sugar levels spiked. It took three months to reduce the levels. At the meetings, only lay users spoke, I never met a doctor or company representative who could advise me about the product.”

Lakshmeesh, an intermittent user of the same product, says he has not developed health problems, but believes only qualified people should advise users. “The sector is highly commercialised now, and people higher up in the chain earn very high commissions.”

In a recent case reported from Mumbai, Clarissa D’mello, 51, took herbal supplements that she found via WhatsApp to cure her diabetes. She started developing health problems within four months, and tests later showed over eight times the permissible levels of lead in her blood. She recovered after a week’s treatment at a private hospital.

Doctors say that even supplements like vitamins and minerals should be taken only if the person has a specific deficiency as per a medical practitioner’s prescription, as indiscriminate use has side effects.

While the public need to be cautious about the necessity and quality of the supplements they use, stringent regulations and enforcement are needed from the authorities too.

(Published 13 August 2023, 00:02 IST)