On the morning of 21 August 2013, a patient with acute liver failure was on the urgent transplant list at Queen Elizabeth hospital, Birmingham (QEHB). If a donor couldn’t be found within 72 hours, she would die. But she got lucky. By 7pm the woman – later known in court as Patient A – was anaesthetised and unconscious on the operating table, with a healthy, deep-red donor liver glistening on ice for her nearby.

QEHB had one of the UK’s leading liver units, and Simon Bramhall, the hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB) surgeon on call that evening, was one of only about two dozen in the country at the time who specialised in liver transplants. At 49 years old, Bramhall had already performed the operation nearly 400 times. On any given day, there would be at least 10 trainees from around the world working with him, learning from his experience. In a centre of excellence, he was one of the best.

Patient A’s surgery was a success. But within a few days it became clear that her new liver was failing, and on 29 August she was back on the operating table for a second urgent transplant. Another HPB surgeon, Bramhall’s colleague, was on call that day. And when he opened Patient A up, he saw, burned on to the surface of the liver she had received during Bramhall’s procedure, in clear characters four centimetres high, two letters: “SB”.

There was no doubt who had burned these initials on to Patient A’s liver. The question was why – and how Simon Bramhall had been able to do it in a brightly lit operating theatre surrounded by nurses, anaesthetists, trainees and other staff.

But the surgeon was not troubled enough by these questions to report his colleague immediately. He took a photograph of the initials, but the images stayed on his BlackBerry for months, while Bramhall continued to perform surgery. Perhaps he didn’t think Bramhall posed any risk to patients: he would have known that the argon beam Bramhall had used to sign his work sears the surface of the liver without harming its function. Yet at some point, the surgeon showed the photograph to others at QEHB, and by 18 December 2013, Bramhall was suspended while University Hospitals Birmingham NHS foundation trust conducted an internal investigation.

A consultant anaesthetist – who had not previously made a complaint about Bramhall signing livers – then reported seeing him initialling the liver of another patient, Patient B, during a transplant on 9 February 2013. A theatre nurse who had been present during the 21 August procedure said she had observed Bramhall signing Patient A’s liver, and asked him what he was doing. Bramhall had told her: “I do this.”

It was the beginning of a very slow end to Bramhall’s career. He didn’t lose his job at QEHB, instead leaving of his own accord after the end of his five-month suspension. He continued to practise surgery in another hospital until June 2020, and was struck off the medical register in 2022, four years after he was convicted of battery for branding the livers of Patients A and B, and almost a decade after his initials were first discovered.

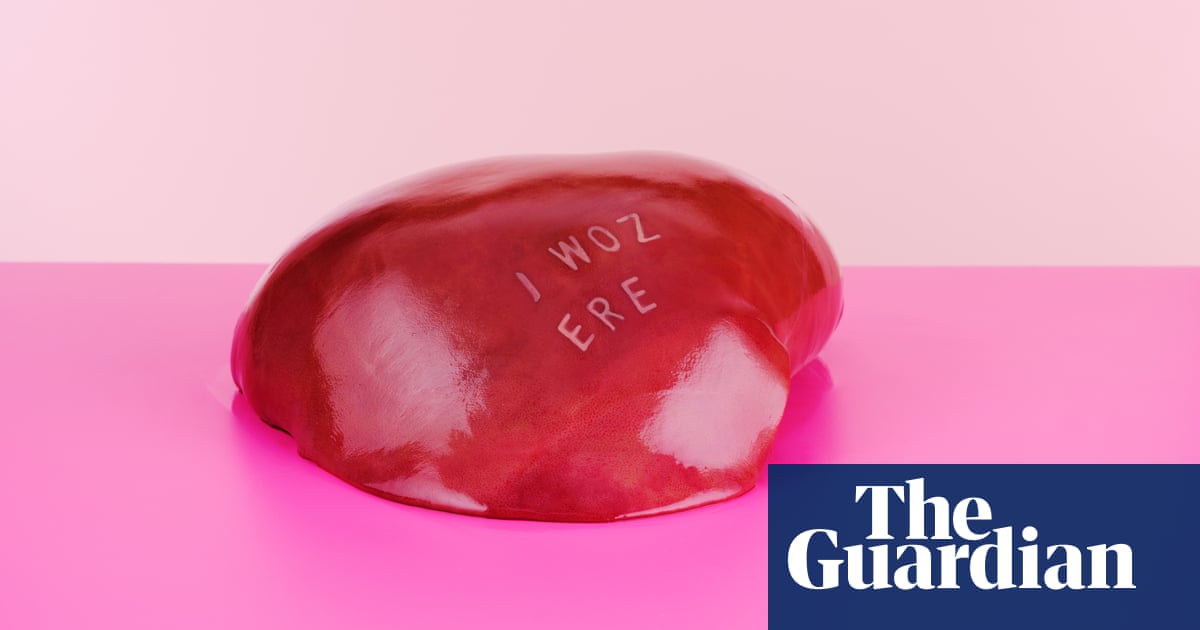

The surgeon who signed his work is now writing books. Bramhall has reinvented himself as an author of self-published medical thrillers, co-written with Fionn Murphy, a former English teacher on whom he once operated. They call their series of books Scalpel Stories. Their latest release – their sixth – is based on what happened with Bramhall and Patient A. It’s entitled Letterman.

Former patients have been unwavering in their support for Bramhall. “I wouldn’t have cared if he did it to me. The man saved my life,” transplant patient Tracy Scriven told the Birmingham Mail in 2014 when Bramhall was suspended. “When I heard the news, my very first words to my wife were, ‘I hope he signed mine’,” Jeff Hughes, 70, told Worcester News in 2017. A JustGiving page set up by a former patient to cover the fine Bramhall received after his criminal conviction raised thousands of pounds in donations. Nearly 900 people signed a petition demanding all charges against Bramhall be dropped and he be reinstated. “Any surgeon possessing pride enough in their work to want to sign it should be celebrated and not vilified” reads the wording above their signatures.

Was it pride that spurred Bramhall to burn initials on to his patients, or something more sinister? If so, why did so many people demand his return to surgery? Is he a bad apple, an embarrassment to his profession, or the product of a broader culture in surgical theatres that encourages and celebrates big egos and allows them to act with impunity? Is Bramhall just the one who happened to get caught?

Bramhall does not like journalists. Just before Christmas 2013, when the news first broke, he remembers lying down with his cheek pressed against his kitchen floor, hiding from the lenses poking over the fence to get a shot of him – a painful fall from grace for someone used to being hailed as a hero. But he has decided to give this interview because of the forthcoming release of Letterman. We speak for several hours on Zoom over patchy broadband from his home in Cornwall, where he now writes his novels. He doesn’t want me to say exactly where he is, or to come to his house, in case it upsets his wife, who is even more wary of media attention than he is.

Bramhall never set out to be a liver surgeon. “I ended up on the liver unit almost by accident, and it was obvious to me that that’s what I wanted to do,” he says. “I was a larger-than-life character, and it was big surgery, proper surgery, cutting-edge stuff, right at the borders of what was technically possible. That’s where I wanted to be – pushing that envelope.” His eyes twinkle behind the thick black frames of his glasses. Then they fall. “I think at the time, that was me, that was my personality. Events change you.”

With his garish ties and flashy SUV, Bramhall had been a big character at QEHB. He had made headlines in 2010 when a Cessna transporting a liver for a patient on the super-urgent transplant list crashed in fog coming in to land at Birmingham airport, bursting into flames. The blackened ice cooler containing the precious liver was recovered from the wreckage reeking of smoke and aviation fuel, and Bramhall was able to use the salvaged organ to perform a successful transplant that evening. “Crashing and burning is not something we normally do with our donor livers,” he remarked at the time.

He worked seven-day weeks on call. There would often be full working days in theatre, followed by transplants until after midnight, before starting again the next morning at 7am. Few hospitals have theatres free during the day, he explains, so most donor organs are retrieved early in the evening or overnight, and then have to be given to the recipient as quickly as possible. “The longer it takes, potentially the poorer the outcome is for the recipient. There’s a lot of pressure.” But it was satisfying work. Liver transplants are visibly transformative for patients: within a few days, their skin will go from yellow to pink as their health returns. Many of Bramhall’s patients – including Patient A – were young. “You are taking somebody who is near to death, and you are giving them an option of a relatively normal life.”

And 21 August 2013 had been one of those days. Bramhall had already performed scheduled surgery on two patients by the time the donor liver became available for Patient A. Her transplant should have been fairly straightforward, he says: she wasn’t overweight, and her failing liver was small and shrunken, making it relatively simple to remove. But getting the donor organ in place proved a serious, unexpected challenge.

When he connected the donor and recipient artery, it failed to pulse. He tried to reconnect it four times, looking with intense concentration through surgical glasses at three times magnification, before realising that the artery must have been damaged when the liver was retrieved from the donor. He found a tiny tear on the inner layer of the donor artery, and managed to cut it back, but it left him with a very short vessel to join to the recipient artery. As he strove to get the blood flowing, his patient’s life hung in the balance.

“I finally got it going. I did it. I got a flow into the liver and I was massively relieved. People know when you’re under pressure: your facial expressions, your body language tells people. The whole theatre goes quiet,” Bramhall says. “There’s a huge cognitive overload on you as this is happening. It’s the sort of level of stress that I would say very few people ever feel. I’m not just saying that as an excuse – I think that’s factual.”

With the transplant an apparent success, he did a “time-zero” biopsy of Patient A’s new liver, taking a sample of tissue at the first opportunity after the transplant; should problems arise later, this would help physicians work out what had gone wrong. He used a large needle to do this, and reached for the argon beam coagulator to cauterise the bleeding. “I held the liver in my left hand,” he begins. “There was a little nobble of blood on the top. I squeeze the liver, stop the bleeding with the argon just for 20 or 30 seconds – let go, make sure it’s still not bleeding. And then what I should have done is put the argon down. But I didn’t.” He can’t bring himself to say what he did.

Instead, he says that he knows one surgeon who “has played noughts and crosses on a liver. He’s written other words on a liver that I’ve seen. I’ve seen people do lots of things on the surface of a liver, on the basis that it’s micrometres of damage. The cellular damage is tiny.” He scratches his face. “When I was training, and during the early part of my consultant period, there was plenty of black humour in operating theatres. There are stories about ophthalmologists putting their signatures on the retina when they are using the laser on retinopathy. I’ve seen orthopaedic surgeons squiggle things in the cement when they’re putting hips in. And I witnessed behaviours that would make your toes curl.” What kind of behaviours? “Surgeons making comments about people who are under anaesthetic. Surgeons throwing instruments at the wall. Surgeons head-butting their assistants across the table.”

All of which is deplorable, of course. But not all of it is the same as branding your initials on an unconscious patient’s liver, regardless of how deep the burn damage is. What was going through his mind when he did it?

“I honestly don’t know.” He shakes his head. “Everyone in the theatre was on edge. The tension was palpable. And I guess, I guess, it was a sort of lighthearted relief of that tension.” A performative flourish, an edgy joke to lighten the mood, a bit of theatre in the operating theatre. He looks down, as if he knows how inadequate this must sound. “Obviously, in hindsight, that was not appropriate and not the right thing to do. But I guess that’s how I was feeling at the time.”

We have to put blind trust in surgeons, more than other doctors – we are asleep when they treat us, after all. We sign consent forms before they operate and trust they will respect our wishes, and our bodies, when we are unconscious.

When I ask Bramhall how he thinks others present felt about what he did, he pauses for a long time. “Well, I don’t know,” he eventually replies. “I had two surgeons opposite me, and I don’t think either of them noticed it. So maybe my attempt at relieving the tension was a pointless exercise.” He says he doesn’t remember being challenged by the nurse who went on to tell the trust that Bramhall had said, “I do this”. If he did say this to her, he says, it was because he must have thought she was asking him about the time-zero biopsy, because not every transplant surgeon bothers to take one. It wasn’t an admission that he signed every transplant he performed? “No, no. Definitely, definitely not.”

What about Patient B, the one whose liver a consultant anaesthetist had reported seeing Bramhall sign in February 2013? “I had no recollection of doing it, and no one else at the operating table on that day had any recollection of me doing it either.” Bramhall claims his legal team advised him to plead guilty to charges against both Patients A and B. But he says it only happened once, according to his recollection. “It wasn’t part of routine practice. It just wasn’t.”

At the time of Patient A’s surgery, it never occurred to him that he was doing something anyone would object to. “We’re talking about midnight now. Physically tired. Forefront of your mind is, let’s get this abdomen closed, let’s get this patient on to the intensive care unit and get home.” He didn’t think anyone outside his operating theatre would see the letters he had burned on to Patient A, anyway, because the burn should have healed within days. He didn’t think about how Patient A might feel about his joke. And he never thought about the donor whose liver he had signed. “Once the liver has perfused [has the blood of the recipient circulating through it] it belongs to the recipient, not the donor,” he informs me matter-of-factly.

Bramhall thinks the black humour he took for granted in operating theatres was a product of the type of people who are drawn to surgery. “Surgeons are at one end of a spectrum of doctors, undoubtedly. It’s what in my day you would have called a type A personality – aggressive, macho. I saw the people who were consultants when I was training, and then I guess I became one myself.”

“All surgeons have skeletons in their cupboards,” the neurosurgeon and author Henry Marsh wrote of Bramhall’s actions. “It is easy to become a little disinhibited when operating – the stress, intense concentration and excitement, and then the relief and sense of achievement if all has gone well, can lead to behaviour that, in the cold light of a courtroom or the gleeful unfrocking of the tabloid pages, appears crass and inappropriate.” Bramhall was a fool, Marsh said, but the reaction to him was overblown. “I have no objection to the fact there is a manufacturer’s logo on the titanium plate with which my broken left leg was fixed some years ago.”

In 2000, a New York obstetrician carved his initials into a patient’s abdomen. In 2010, a California gynaecologist was sued after he allegedly used a cauterising device to burn his patient’s name on to her uterus. Bramhall is not the only surgeon to have marked a name on a patient – but he’s the only British one to be sanctioned for it.

Troubling behaviour in British surgical theatres has only recently come under public scrutiny. In September 2023, the Working Party on Sexual Misconduct in Surgery published a report into problems in UK theatres – where the ratio of male to female surgeons is now 8:1. Nearly two-thirds of the female surgeons who responded to the WPSMS survey said they had been sexually harassed in the past five years, and a third had been sexually assaulted. Consultant surgeon Tamzin Cuming, who co-authored the report, sees Bramhall’s actions – and the delay in him being struck off – as evidence of a culture of impunity that persists more than a decade after Patient A’s liver was signed. “He wouldn’t have done it secretly,” she tells me. If any of the other people in the operating room had seen him, she adds, “either they were appalled and they didn’t feel empowered to report it, or it’s normalised and accepted that anything these prima donna surgeons say goes”. Cuming draws parallels with a female surgeon who told the BBC last September about the senior male surgeon who wiped his sweaty face on her breasts during a procedure. “That was not hidden in an office – that was in front of everyone in surgery. He was not struck off. He is still practising.”

In a highly hierarchical environment like a surgical theatre, speaking up can come with real consequences. “People still don’t report because they think nothing will happen,” Cuming says. “And we know what happens to whistleblowers in the NHS – quite often, they end up losing their own jobs.”

When Bramhall first got hauled into his manager’s office, he says he got a telling off. “I apologised profusely and he accepted that.” But when other people at QEHB came to see the photograph of the branded liver after the other HPB surgeon started to share it, a suspension pending an investigation became inevitable. The trust’s panel ultimately issued Bramhall with a written warning, and the GMC ruled that he should remain on the medical register. “This failing in itself is not so serious as to require any restriction on Mr Bramhall’s registration,” it said. But Bramhall no longer felt welcome at QEHB, and left to work as a consultant general surgeon at the County hospital in Hereford.

The trust informed Patients A and B about what Bramhall had done. They accepted that Patient B’s liver had also been signed, on the basis of the statement given by the anaesthetist. The GMC noted that the news had “no emotional impact” on Patient B, but that Patient A had an “extreme, enduring” reaction to it. In 2017, the CPS produced a report from a psychologist who said that Patient A was experiencing symptoms of PTSD, and they then decided to charge Bramhall with actual bodily harm.

“The horror of seeing the photo of my cut-open body with the initials ‘SB’ on the liver will for ever live in my mind. I personally hate the thought of tattoos, anyway, and the thought of someone doing this to me while I was unconscious is abhorrent,” read the victim impact statement she gave in Bramhall’s criminal trial. “It was what I would imagine the feeling is for someone who is a victim of rape … Because of my ordeal, my trust in doctors has been destroyed.”

The decision to charge Bramhall because of Patient A’s trauma “caused a number of raised eyebrows”, he says. “First of all, she was asleep – you have to be aware of it happening. Secondly, there was the causation pathway: she was told by a third party that this had happened. Wasn’t the PTSD caused by the person who told her?”

Surely he can understand that the disclosure was possible only because he burned his initials on to her when she was unconscious?

“I understand that,” he replies immediately. “But, if you look at rules about duty of candour, if there is no harm, you don’t need to tell them. There was always this question of – did she need to be told at all?”

after newsletter promotion

He pleaded guilty to the lesser charge of battery, and was sentenced to 120 hours of community service and a £10,000 fine. “This was born of professional arrogance of such magnitude that it strayed into criminal behaviour,” the judge, Paul Farrer QC, said. “What you did was an abuse of power and a betrayal of trust.” Bramhall says that hearing these words in court was harder to endure than the death of his parents.

But when I ask whether he felt remorse for Patient A, he shrugs. “I was ashamed at what I’d done, but I wouldn’t have done anything that I thought would have harmed the patient. I knew that. And I knew that I’d saved her life, because without the liver I had put in, she would have been dead.” There is a sense, when speaking to Bramhall, that he defines success in terms of surgical outcomes; that he sees harm in a purely physical way.

While Bramhall served his hours of community service steaming clothes in a charity shop in Ross-on-Wye, the GMC wrote to inform him that his fitness to practise was to be reassessed. In December 2020, a medical practitioners tribunal ruled once again that Bramhall should remain on the medical register. But then the GMC struck him off in January 2022, on the grounds that his actions undermined public trust in the medical profession.

Even if he posed no harm to patients, doesn’t Bramhall see how continuing to practise would have harmed public confidence in doctors?

“I did continue to practise for a long time, though, didn’t I? From 2013 right through to 2020. I sat in front of many hundreds of patients, some of whom realised who I was, and didn’t give a monkey’s. At most, there were one or two patients who declined to see me.”

Bramhall sees himself as a fall guy after a decade where men with “type A personalities” have faced a reckoning in almost every profession. “I think the GMC were using me as an example,” he says. “I don’t think anyone has gained from this. The general public certainly hasn’t. My training has cost millions.” The prosecution fees will have cost millions, too, he adds. He has scoured the internet reading the public response to what he did. “I’m not saying everyone is supportive – certainly not – but it’s not black and white. A lot of people are saying: slap his wrist, get him back to work.”

Barbara Moss first read about what Bramhall had done six years after he had operated on her liver. “I thought, this is terrible,” she tells me over Zoom from her home in Worcester. Terrible for the patient? “A terrible thing to happen to Simon,” she clarifies.

She first met Bramhall in 2007, when she was 52, and had just been diagnosed with stage 4 bowel cancer. She had a 15cm tumour in her liver and had been given three months to live. “There was no hope, that was basically it,” her husband, Mark, says. “It was palliative care, only.”

“Simon was the one who said if that tumour in the liver shrinks away from the carotid portal vein, then he would be prepared to operate,” Barbara tells me. He recommended a £20,000 cancer drug that shrank her tumour enough for surgery. Then she had a five-hour operation, during which the left lobe of her liver, her appendix and parts of her colon were removed. “Simon was very direct. He told me, there’s a 50-50 chance of dying in the operation,” she says. “I was so lucky to be given that chance.”

Seventeen years on, Barbara is cancer free, and she and Mark now do patient-advocacy work. The operation she had is no longer performed. “There’s too high a risk,” Barbara says. “But Simon pioneered it, and I am alive because of it.” She sees Bramhall’s boldness and willingness to push boundaries – his “type A personality” – as a critical factor in saving her life.

Barbara gave evidence in Bramhall’s case, telling the judge that the packed courtroom would be empty had Bramhall not saved the lives of the former patients that filled it. And it was Barbara who set up the JustGiving page to cover his fine (Bramhall insisted that the few thousand pounds that were raised went to the British Liver Trust, she says). “I’d give my life for him,” she tells me.

If you believe you owe someone your life, you might be willing to excuse them anything. But two things can be true at the same time – Bramhall saved scores of lives, and also did an inexcusable thing.

Barbara thinks there is nothing to excuse. “He’s got to test the laser on the liver before he can use it – it’s a routine process. If I’m trying out a pen, I might as well just put my initial, because I can do that very quickly. The fact that he did it in a particular shape makes no difference.”

Ultimately, she says, it is patients who lose out. “He has that sort of experience that meant he is not replaceable. England has been deprived of his expertise. It has prevented the chance of thousands of other people’s lives being saved, or at least made better. I feel it’s scandalous.”

“Simon Bramhall was an extremely good liver transplant surgeon, with an extremely positive reputation,” says Prof Mark Taylor, consultant HPB surgeon in Belfast Trust, and former Northern Ireland director for the Royal College of Surgeons. “For someone who has gained that level of experience … the answer is that people would lose out. But anything that gives the impression that surgeons believe they are untouchable because they possess a certain set of skills causes harm. The fundamental practice of medicine is that people put their trust in you at their most vulnerable. If that is inhibited, then it is individuals in ill health who will suffer the most.”

Taylor never worked with Bramhall but knew of him, and followed the various excuses that Bramhall and others have given to explain what he did. It’s true the burn caused no real damage to the liver, and that surgeons routinely test the argon beam on the surface of the organ before they use it, but this is “a very small wiggle or a couple of dots to show that it’s working”, not an autograph, and testing happens before there is any bleeding to cauterise, not after.

“The aggressive surgeons that we’ve all had in our training, the many horror stories we could all give – those days are no longer tolerated. It is incumbent on all of us – and as a white, middle-aged, male surgeon I think it’s really important – that we have that culture where junior colleagues can call out inappropriateness without fear of sanction. Thankfully, the world we’re now in is much healthier.”

When Bramhall was convicted, the Royal College of Surgeons of England released a statement saying there was “no evidence that this practice is widespread in surgery”. Does that mean it may happen, even if it doesn’t happen often? “I’m in my 30th year of medicine, I’ve never seen anyone do some sort of character or noughts and crosses on the liver,” Taylor replies. “Branding your initials on a liver is a very peculiar thing to want to do.”

Bramhall is adjusting to life outside the surgical theatre. “I have a wonderful wife who is incredibly supportive, and I’ve dragged her through an awful time. Without her, I don’t think I’d have been here.” At 59, he would have been coming up to retirement age, anyway. He will soon draw his NHS pension.

He sees the six books he has written with Murphy as a kind of therapy. Bramhall and Murphy had bonded over his jokes about the hospital food after he removed a grapefruit-sized tumour from her in an eight-hour procedure in 2012. But they got to know each other properly after Murphy set up the “Save Our Surgeon: Bring Back Simon Bramhall” Facebook page.

“When I saw it on the news, my initial reaction was to laugh. I thought it was hilarious – I know you probably shouldn’t say that,” Murphy says sheepishly. “I couldn’t believe what he’d done. He shouldn’t have done it – he knows he shouldn’t have done it, we all know he shouldn’t have done it. But the media reaction, I felt, was utterly hysterical. He could have written his name, address and autobiography on me – I don’t care. I’m alive.”

Murphy set up the Facebook page as a forum for “people like me to be able to say, ‘He’s not a bad man. This isn’t fair.’” She can’t tell me how many people signed up to it – the page doesn’t exist any more, having been repurposed as a fan page for their Scalpel Stories series – but there were “hundreds and hundreds and hundreds”, not only patients and their families but also medical staff who had worked with Bramhall, as well as sympathetic members of the public. “I was staggered by the response. I had no idea what I’d unleashed.”

To keep the group updated on the state of Bramhall’s various legal fights, Murphy stayed in regular contact with him over email and WhatsApp. “She understood the effect all this was having on me,” Bramhall tells me. “We talked about it. I said I thought I’d like to write it down, that that would be cathartic for me, and she said, ‘OK, shall we do that together?’”

They wrote Letterman first. “It’s a fictionalised version of events,” Bramhall says. But the GMC was still assessing his fitness to practise when they completed it, so they set it aside and got to work on other novels, all based on Bramhall’s experiences. Dilemma (2020) is about organ donation; the opening scene involves someone eating liver and onions in a cafe. Charity (2019) is inspired by some of what Bramhall encountered while doing community service. Seeing their self-published books selling on Amazon, and holding the hard copies in his hands, felt like an achievement for Bramhall: he was able to feel pride in his work once more. And since, as he puts it, “the GMC can’t strike me off again”, they have decided it’s time to publish Letterman.

They let me read an unfinalised version of their manuscript. Alex – a star surgeon with bright ties who revels in the glory of high-risk success – is victimised by a professional rival at his hospital. In a moment of high stress, he burns his initials on to the liver of a male patient. The patient has no redeeming qualities: no friends, no one to visit him, no appreciation that his life has been saved. He is a professional actor, and his trauma on discovering what Alex did is a performance; when his victim statement is read out in court (including some of the same language used in Patient A’s statement – even though there was never any suggestion that Patient A was inventing her trauma, and only sympathy, rather than any criticism, was expressed for her in court), people scoff in disbelief. Another patient – a young mother – dies because Alex’s suspension means a less experienced surgeon does her transplant.

As I read, I become aware just how well worn the story Bramhall told me over Zoom was. It is not just the details and characters that are familiar, but the words, too. The “black humour” of operating theatres. The “palpable tension” during surgery. The other surgeons who “played noughts and crosses” on a liver or “signed their initials on retinas”. He has had a decade to hone this story, before the trust, the courts, the GMC and in this manuscript, and, finally, to me.

At first it looks as if it is Alex the surgeon who has been branded – as a criminal – rather than his victim. But he pulls through to become an award-winning, bestselling author. Someone “who signs books instead of livers”, as Alex says. This is how Bramhall would like his ending to be. When you write the story, you control it, after all.

Bramhall may have been arrogant, Murphy says, but events have changed him. “He’s terribly remorseful – and I think that’s the saddest thing, actually, because there’s nothing he can do about it.” They both know that the release of Letterman will bring him fresh scrutiny. “I’m nervous on his behalf,” she says. “I don’t think I’ve got his bottle.”

I ask Bramhall why he isn’t writing under a pseudonym. “We talked about that, but in the end the name has helped sell the books – it’s helped more people know about them,” he replies. Having read the findings of every investigation, every report and every online comment, is he not tempted to keep his name off things now? “I probably should have slipped away into oblivion,” he smiles. “But I guess I’m not that type of person.”